Scientists have given robots a ‘brain’ so they can self-repair when they detect pain

Using artificial intelligence (AI), scientists at the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, have developed a way for robots to recognise pain and to self-repair when damaged.

The scientists adopted a brain-inspired approach when creating the system and as a result, the robot is able to repair its own damage without any human interference. Using AI-enabled sensor nodes, the robots will also be able to process and respond to pain that arises from pressure exerted by a physical force.

This technology allows robots to use a network of sensors in order to generate information about their immediate environment. For example, the disaster rescue robot will use a camera and microphone sensor to locate a survivor stuck under debris and will pull the person out with guidance from touch sensors on their arms.

Current sensor technology does not process information but instead sends it to a single central processing unit where learning then occurs. As a result of this technological set back, existing robots will experience a delayed response time and be susceptible to damage due to being heavily wired. This will often require maintenance and repair which can be a long and costly process.

To combat this challenge, i.e. making sure the learning happens locally, AI is embedded into the network of sensor nodes, connected to multiple small, less-powerful processing units that act like ‘mini-brains’ distributed on the robotic skin. Local wiring reduces response time for the robot five to ten times compared to conventional robots.

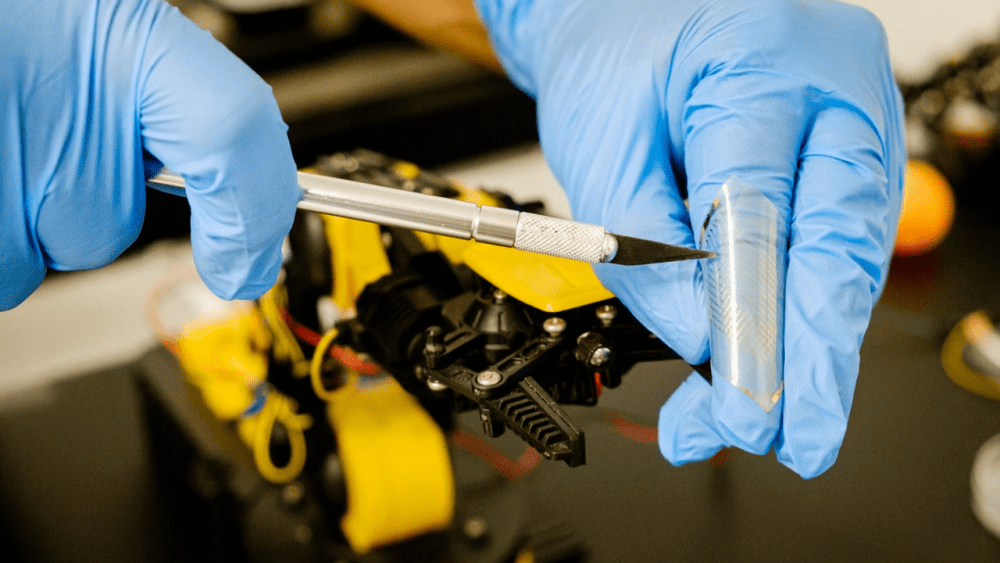

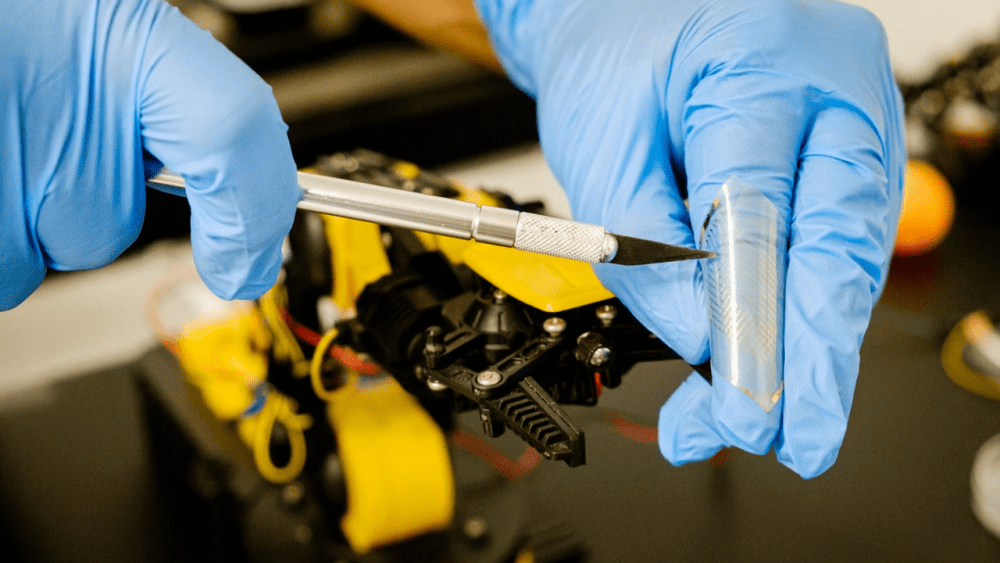

The scientists have combined this system with a type of self-healing ion gel material that allows the robots, when damaged, to recover their mechanical functions without interference from humans.

Co-lead author of the study, Associate Professor Arindam Basu from the School of Electrical & Electronic Engineering said:

For robots to work together with humans one day, one concern is how to ensure they will interact safely with us. For that reason, scientists around the world have been finding ways to bring a sense of awareness to robots, such as being able to ‘feel’ pain, to react to it, and to withstand harsh operating conditions. However, the complexity of putting together the multitude of sensors required and the resultant fragility of such a system is a major barrier for widespread adoption.

The research team fashioned memtransistors – ‘brain-like’ electronic devices, to teach the robots how to recognise pain. These devices act as artificial pain receptors and synapses that are capable of memory and information processing. When the robot is ‘injured’, having been cut from a sharp object, it quickly loses mechanical function; this is when molecules in the self-healing ion gel begin to interact, causing the robot to begin ‘stitching’ its ‘wound’ together to restore its function, all while maintaining high responsiveness.

Associate Professor Nripan Mathews, who is co-lead author and from the School of Materials Science & Engineering at the university, said:

In this work, our team has taken an approach that is off-the-beaten path, by applying new learning materials, devices and fabrication methods for robots to mimic the human neuro-biological functions. While still at a prototype stage, our findings have laid down important frameworks for the field, pointing the way forward for researchers to tackle these challenges.